International Commercial Arbitration Q1 2024

This update explores trends and developments in international commercial arbitration seen from a Norwegian perspective.

A fully booked Norwegian Arbitration Day (NAD) was held on 8 February 2024, in addition to pre-events at the law firms BAHR and Wiersholm and a post-event hosted by the law firm Schjødt. Since its inception in 2019, NAD has already grown to become an important meeting place for arbitration practitioners in the Nordic countries.

In this Q1 2024 newsletter, we will look into the following themes raised during the NAD-events:

- Best practice for the arbitral tribunals’ decision-making process

- An update regarding use of sealed offers to promote settlements

- An overview of the Nordic Project regarding challenging of arbitral awards

Furthermore, we will, as always, provide the latest NOMA News and highlight What’s On the Agenda.

We hope you like it!

Best Practice for Decision Making Processes in International Commercial Arbitration

Background

As a pre-event to NAD 2024, Wiersholm held a seminar and panel debate with the main theme:

“Best practice for decision-making processes”

Intuitively, and also backed by research, an arbitral tribunal of three is more reliable than that of a single arbitrator. However, research also shows that all decisions made in a group – be it arbitration tribunals, courts, or a team of lawyers – run the risk of being influenced by collective thinking, confirmation bias and other pitfalls.

The event was kicked off by psychologist Jan Ole Hesselberg. Hesselberg has authored the book “Better Decisions” (Nw.: “Bedre beslutninger“), and has frequently aired his views on the dangers of collective thinking in decision-making processes. Recently, he questioned the voting method in the Norwegian Supreme Court – where he asked, among other things, whether the method was based on research or tradition.

In his presentation at the pre-event (which can be viewed here) Hesselberg highlighted three core “test” questions for groups taking decisions together:

- What is the goal of the decision-making process?

- Do the steps in your process bring you closer to your goal? (Hunches, assumptions and traditions do not constitute evidence)

- Is the cost worth the benefit?

Following Hesselberg’s presentation, Supreme Court Judge Erik Thyness, former Supreme Court Justice of Sweden and professor II on the Scandinavian Institute of Maritime law Johnny Herre and esteemed arbitration practitioners Kristoffer Löf (Mannheimer Swartling) and Peter Schradieck (Plesner) discussed the topic based on their experiences from both the ordinary courts and international arbitration.

As a follow up of the discussions during this pre-event, Advokatbladet (the Norwegian lawyers’ journal), published an article with the title “Equal treatment is utopia“, see here. The article i.a. provides further reference to relevant research and articles and the Supreme Court’s reply to Jan-Ole Hesselberg’s above mentioned critique.

What’s the goal of an Arbitral Tribunal’s decision-making process?

Using the above “test” questions as a starting point, the first main question is: What is the goal of the decision-making process for an arbitral tribunal?

During an arbitration process, the arbitral tribunal may have to decide on many issues and procedural disputes up to and through the main hearing. However, if the parties’ dispute is not resolved during the pre-arbitration process, the main goal for the arbitral tribunal is to decide on the merits of the case and to provide the parties with a final, enforceable award (including a decision on allocation of costs).

The Norwegian Arbitration Act does not provide any guidance on how the arbitral tribunal should structure its decision-making process, and based on our knowledge, there are no institutional rules addressing this. Consequently, it is very much up to the tribunal, and especially the chairperson, to potentially structure the decision-making process to avoid the pitfalls of collective thinking and to secure that all relevant arguments and angles are considered when deciding on the merits of the case in accordance with the applicable law, cf. the section 31 of the Norwegian Arbitration Act.

The jury is still out on what is best practice in international commercial arbitration, but we will share our thoughts on the main elements below.

Wiersholm’s view on best practice for Arbitral Tribunals’ decision-making processes

Focusing on the phase which the arbitral tribunal has heard all the evidence and is to decide on the merits of the case, we believe that the following should be implemented to avoid the pitfalls of collective thinking and secure the most correct award:

First, the initial discussions between the members of the tribunal should focus on getting all the main pro- and con arguments on the table for each of the main decision points in the case. At this stage there should be no “conclusion”-talk regarding what the respective arbitrators believe is the correct decision on the different main decision points. If there are disagreements within the tribunal on what the main decision points are, this should evidently first be established. A powerful tool for establishing and visualising the main decision points is the use of decision trees. The use of decision trees is also recommended by the ICC in its publication “Effective Conflict Management” published July 2023, see here. There, the key tasks in a decision tree analysis are described as follows:

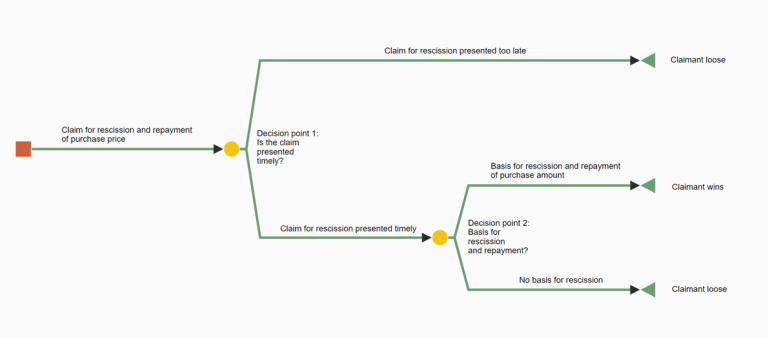

Here is an example of a (simple) decision tree in a case where the claimant has raised a claim for recession and repayment of the purchase amount, and the respondent has argued that the claim is presented too late, and in any case that there is no basis for the claim:

Illustration: Wiersholm, by use of dNodes.io

As a second step, and in line with the ICC model above, each member of the tribunal should individually assess what they believe is the correct outcome for each main decision point. The arbitrators’ individual views should be written down as preparation for the final and third step. A potential add-on exercise here, is to indicate how certain one is regarding the outcome on each decision point by using percentages.

As a third and final step, the tribunal should meet and finally decide on the merits of the case. During this step, the chairperson should try to facilitate a structured discussion where the least senior member of the tribunal starts by presenting his/her view – to avoid the authority bias (Nw: autoritetsfellen). This is in line with the system used in both the Swedish and Danish Supreme Courts. Following an initial round of hearing each arbitrator’s view, it is in our opinion difficult to provide much more specific guidelines on how the discussions should be organised before the tribunal reaches its final conclusions.

Sealed offers – an update

In our Q3 2023 newsletter, we gave an overview of the use of sealed offers in international commercial arbitration, and argued that this may serve as a good mechanism to encourage early resolution of disputes within the arbitration process. However, as we also pointed out, there is no established best practice for defining specific mechanisms to be included in the PO1 or terms of reference in international arbitration.

It is thus noteworthy that the topic of sealed offers was discussed during the Norwegian Arbitration Day 8 February 2024. During the panel debate on “Amicable Settlements and mediation in arbitration”, Leilah Bruton provided an overview on the use of Part 36-offers in the ordinary courts in the UK and how sealed offers can be used in international arbitration, see her presentation here. Subsequently the other panelists, Madelein Thörn, Mathias Steinø and Christian Hauge (with Ola Nisja as moderator), argued that the use of sealed offers may be an efficient mechanism. It was also highlighted that the NOMA rules constitute the only Nordic standard which states that a rejected settlement offer “shall” be taken into account in the arbitral tribunal’s cost ruling, see NOMA’s LinkedIn-post on the matter here.

For sealed offers to serve as an efficient mechanism for encouraging early settlement (and thus saving costs), it is necessary to further develop best practice for how to regulate this in the PO1 or terms of reference. As we highlighted in our Q3 2023 newsletter, inspiration can be found in the Society of Maritime Arbitrators (SMA) Arbitration Rules as of June 2022 (SMA Rules 2022) which incorporate the concept of sealed offers in Section 31(d).

We will continue to update you when we see further noteworthy developments on this topic.

Challenging Arbitral Awards

The Nordic law firms Punct, Castrén & Snellman, Wikborg og Rein and Westerberg have issued a report on challenged arbitral awards from Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland in 2023 – which was presented during the Norwegian Arbitration Day.

The aim of the report is to explore and summarise the extent to which arbitral awards are contested in the Nordic countries, and the success rate of such challenges. The report’s findings show that:

- The number of challenged cases is very low, and successful challenges are uncommon in all Nordic countries.

- The legal systems in the Nordic countries and the courts are arbitration friendly, and the bar for challenging an arbitral award is set high.

- In 2023, a total of 22 challenged cases were decided in all four countries (some are still subject to possible appeal). Two challenged cases were successful, both seated in Sweden. Four challenges cases were settled, all seated in Sweden.

- The report illustrates that awards are set aside or annulled only in exceptional circumstances pertaining to breaches of the most fundamental procedural principles.

A link to the full report can be found here.

NOMA-news

On LinkedIn, NOMA reports that yet another award in a marine fuel supply dispute has been rendered, see here. NOMA also reports that it has witnessed a particular uptake in marine fuel-related cases, and arbitrators appointed under NOMA rules are building up strong expertise in this specialised domain.

Regarding the award in question, NOMA reports that despite facing various procedural challenges, the award was delivered nine months after the initiation of arbitration. This achievement demonstrates that timely, fair, and effective resolutions in the landscape of marine fuel disputes can be obtained under the NOMA rules. NOMA invites stakeholders in the marine fuel industry to look to NOMA for efficient dispute resolution mechanism, and refers back to a previous post on Stem Fuels’ choice of NOMA in their Terms and Conditions.

What’s on the Agenda

Roschier Dispute Index 2024 published

The seventh edition of the Roschier Disputes Index has recently been published, which is a comprehensive market survey that focuses on the current practices and trends in dispute resolution among major corporations in the Nordic region. The Roschier Disputes Index aims to track and analyse how the largest Nordic companies approach and manage commercial dispute resolution.

This edition continues to delve into preferred dispute resolution methods, arbitration rules, substantive laws, and practical dispute management strategies. In addition to these traditional areas of focus, the 2024 edition also addresses current global issues impacting dispute resolution, such as ESG and the implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A highlight of this year’s edition is a 10-year comparison of results in certain sections, showcasing the value of the responses collected over the years and the longevity of the Index. We believe that the Roschier Disputes Index serves as a valuable resource for management, general counsel, external counsel, and for anyone interested in dispute resolution in the Nordics. We highly recommend interested colleagues and clients to give it a read. A link to the Roschier Disputes Index can be found here.

IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration 2024 version published

As we have previously touched upon in our Q2 2023 newsletter, a fundamental principle in arbitration, is that the arbitrators shall be impartial and independent of the parties, cf. the Norwegian Arbitration Act (NAA) section 13, first paragraph.

In the process of establishing a tribunal, the potential arbitrators are, as a first step, obliged to disclose circumstances likely to give rise to justifiable doubts as to his or her impartiality or independence. This obligation persists throughout the arbitration procedure, cf. the NAA section 14, first paragraph.

If one of the parties challenges the impartiality or independence of an appointed arbitrator, and the arbitrator does not voluntarily withdraw, the appointed tribunal will as a second step consider the challenge, cf. the NAA section 15, first paragraph.

If the appointed tribunal dismisses the challenge, and the parties have not agreed to a different procedure, the challenging party may as a third step bring the issue before the ordinary courts. The decision of the first instance court is binding and may not be appealed, cf. NAA section 15, second paragraph.

The assessment of whether there exist justifiable doubts about an arbitrator’s impartiality or independence, can be difficult in practice. To assist making a correct assessment, the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration (“the Guidelines”) have since their inception in 2004 been an important soft-law tool reflecting international standards for arbitrators’ impartiality and independence. The Guidelines are a relevant source of law when interpreting the NAA, cf. HR-2017-1932-A, paragraph 113, and Tørum, “‘Best Practice’ i norsk og nordisk voldgift og NOMAs Guidelines” in Tidsskrift for forretningsjus, 2018 p. 111 ff., p. 114.

The Guidelines were updated in 2014 and now in 2024. The 2024 version was published in February, and can be accessed here.

Without going into the details, we highlight the following updates in the 2024 version of the Guidelines:

- The new General Standard 3 (e) sets out that if an arbitrator finds that the arbitrator should make a disclosure, but that professional secrecy rules or other rules of practice or professional conduct prevent such disclosure, the arbitrator should not accept the appointment, or should resign.

- The new General Standard 3 (g) clarifies that an arbitrator’s failure to disclose certain facts and circumstances that may, in the eyes of the parties, give rise to doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence, does not necessarily mean that a conflict of interest exists.

- According to the General Standard 4 (a), ii), a party must at the outset raise an objection within 30 days if it has knowledge of facts or circumstances that could constitute a potential conflict of interest for an arbitrator. The new General Standard 4 (a), second paragraph, clarifies the parties’ due diligence obligations: A party shall be deemed to have learned of any facts or circumstances under 4(a)(ii) that a reasonable enquiry would have yielded if conducted at the outset or during the proceedings.

On the international commercial arbitration scene, there are many events to choose from. We recommend considering the following upcoming happenings:

- 25 April 2024 (Helsinki): Social networking event preceding Nordic Arbitration Day

- 26 April 2024 (Helsinki): Nordic Arbitration Day – a full-day arbitration conference for young arbitration practitioners (aged 45 or under) organised by YACF in collaboration with the other young Nordic arbitration associations

- Please also mark your calendar now for the second NOMA Day, which will be held in Copenhagen on 10 October 2024

Read our newsletter on International Commercial Arbitration for Q4 2023 here.

Key Contacts

Published:

Last modified: